Costochondritis

Conditions

Overview

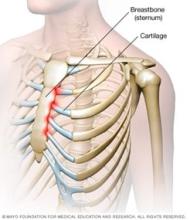

Costochondritis (kos-toe-kon-DRY-tis) is an inflammation of the cartilage that connects a rib to the breastbone, called the sternum. Pain caused by costochondritis might be like that of a heart attack or other heart conditions.

Costochondritis is sometimes called chest wall pain syndrome, costosternal syndrome or costosternal chondrodynia. Sometimes, there is swelling with the pain, which is a condition called Tietze syndrome.

What causes costochondritis is unclear. Treatment focuses on easing the pain while waiting for the condition to improve on its own. This can take several weeks or more.

Symptoms

The pain associated with costochondritis often:

- Is sharp or aching or feels like pressure.

- Can radiate to arms and shoulders.

- Worsens when taking a deep breath, coughing or sneezing, or with any movement of the chest wall.

- Affects more than one rib.

- Happens on the left-hand side of the breastbone.

When to see a doctor

For chest pain, seek emergency medical attention to rule out life-threatening causes, such as a heart attack.

Causes

Costochondritis often has no clear cause. However, it might be associated with trauma, illness or physical strain, such as severe coughing.

Risk factors

Costochondritis happens most often in women over age 40.

Tietze syndrome, when there is swelling with the pain, often happens in teenagers and young adults, and with equal frequency in men and women.

Diagnosis

During the physical exam, a healthcare professional feels along your breastbone for tenderness or swelling. The health professional also might move your rib cage or your arms in certain ways to try to trigger symptoms.

The pain of costochondritis can be like the pain associated with heart disease, lung disease, gastrointestinal problems and osteoarthritis. There is no laboratory or imaging test to confirm a diagnosis of costochondritis. But a healthcare professional might order certain tests, such as an electrocardiogram and chest X-ray, to rule out other conditions.

Treatment

Costochondritis often goes away on its own, although it might last for several weeks or longer. Treatment focuses on pain relief.

Medicines

Your healthcare professional might recommend:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. You can buy some types of these medicines, such as aspirin, naproxen sodium (Aleve), ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or acetaminophen (Tylenol, others), without a prescription. Stronger versions are available by prescription. Side effects can include damage to the stomach lining and kidneys.

- Narcotics. If pain is severe, you might need a narcotic such as tramadol. Narcotics can be habit-forming.

- Antidepressants. Tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, are often used to manage chronic pain — especially if the pain interferes with sleep.

- Anti-seizure drugs. The epilepsy medication gabapentin (Gralise, Neurontin) has proved successful in managing chronic pain.

Therapies

Physical therapy treatments might include:

- Stretching exercises. Gentle stretching exercises for the chest muscles might be helpful.

- Nerve stimulation. Using transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, also known as TENS, may help reduce pain. The TENS unit is a device that sends a weak electrical current through adhesive patches on the skin near the area of pain. The current might interrupt or mask pain signals, preventing them from reaching the brain.

Surgery or other procedures

If conservative measures don't work, another option is to inject numbing medicine and a corticosteroid directly into the painful joint.

Self care

It can be frustrating to know that there's little to do to treat costochondritis. But self-care measures, such as the following, might help.

- Nonprescription pain relievers. Aspirin, naproxen sodium (Aleve), ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) may be helpful.

- Topical pain relievers. These include creams, gels, patches and sprays. They may contain nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or numbing medications. Some varieties contain capsaicin, the substance that makes hot peppers spicy.

- Heat or ice. Try placing hot compresses or a heating pad on the painful area several times a day. Keep the heat on a low setting. Ice also might be helpful.

- Rest. Avoid or modify activities that might worsen pain.

Preparing for your appointment

You may be referred to a doctor who specializes in disorders of the joints, called a rheumatologist.

What you can do

Ask a relative or friend to come with you, to help you remember what your healthcare team says.

Make a list of:

- Symptoms, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for the appointment, and note when they began.

- Key medical information, including other conditions you have and any injury to the painful joint.

- Key personal information, including major life changes or stressors.

- All medications, vitamins and supplements, including the doses.

- Questions you may have for the healthcare team.

Questions to ask your doctor

- What's the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- What tests do I need?

- What self-care steps are likely to help?

- Do I need to restrict activities?

- What new signs or symptoms should I watch for?

- When can I expect my symptoms to resolve?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare team is likely to ask you a number of questions, including:

- Have your symptoms worsened over time?

- Where is your pain?

- Does exercise or physical exertion make your symptoms worse?

- Does anything else make your pain worse or better?

- Are you having difficulty breathing?

- Have you had recent respiratory infections or injuries to your chest?

- Are you aware of a history of heart problems in your family?

© 1998-2026 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research(MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use