Laryngotracheal reconstruction

Procedures

Overview

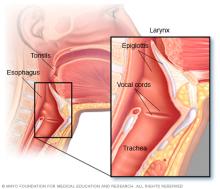

Laryngotracheal (luh-ring-go-TRAY-key-ul) reconstruction surgery widens the windpipe or voice box to make breathing easier. The windpipe also is called the trachea and the voice box also is called the larynx. Laryngotracheal reconstruction involves placing a small piece of cartilage into the narrowed section of the windpipe to make it wider and stay open. Cartilage is stiff connective tissue found in many areas of the body.

A narrowed windpipe is most common in children, but it can happen in adults.

The goal of laryngotracheal reconstruction is to provide a safe and stable airway without needing a breathing tube.

Why it's done

The primary goal of laryngotracheal reconstruction surgery is to create a permanent, stable airway for breathing without the use of a breathing tube. Surgery also can help with voice and swallowing issues.

In people who already have a tracheostomy tube to help them breathe, this procedure often makes it possible to get rid of the tracheostomy. A tracheostomy is a hole that a surgeon makes through the front of the neck and into the trachea. A tracheostomy tube is placed into the hole to keep it open for breathing.

In children, a narrowed windpipe may happen from injury or infection. It also may be a condition found at birth or a condition that results from having a breathing tube.

An adult's windpipe can become narrowed for the same reasons. Also in adults, a narrowed windpipe can happen from diseases that cause blood vessel or tissue irritation and swelling. Examples of these diseases are sarcoidosis or granulomatosis with polyangiitis, previously called Wegener granulomatosis.

Reasons for this surgery include:

- Narrowing of the airway. Narrowing of the airway, also called stenosis, may be caused by infection, disease or injury. But it's most often due to irritation caused by putting in a breathing tube in babies. A breathing tube may be placed in babies with conditions present from birth, who are born prematurely or who need a medical procedure. Stenosis can involve the vocal cords, called glottic stenosis; the windpipe just below the vocal cords, called subglottic stenosis; or the main part of the windpipe, called tracheal stenosis.

- Changes in the way the voice box developed. Rarely, the voice box, also called the larynx, is not fully developed at birth or may be narrowed by extra tissue growth present at birth. Changes in the larynx also may be caused by scarring from a medical procedure or infection.

- Weak cartilage in the windpipe. When a baby's soft, immature cartilage is not stiff enough to keep the airway open, the walls of the windpipe can weaken and sometimes fall in. This makes it very difficult for the child to breathe.

- Vocal cord paralysis. When one or both of the vocal cords don't open or close properly, the trachea and lungs are not protected when swallowing. Sometimes the vocal cords can partly block the airway and make it hard to breathe. Vocal cord paralysis can be caused by injury, disease, infection, previous surgery or stroke. In many cases, the cause is not known. Some children may be born with this problem.

Risks

Laryngotracheal reconstruction is a surgery that carries some risks, including:

- Infection. Infection at the surgical site is a risk of all surgeries. Call your healthcare professional right away if you notice redness, swelling, or pus from a surgery site or for a fever of 100.4 degrees F (38 degrees C) or higher.

- Collapsed lung. A collapsed lung, also called a pneumothorax, happens when the lung is injured during surgery. Air leaks into the space between the lung and chest wall. This air pushes on the outside of the lung and makes it fall in. This is not a common complication.

- Shifting of a breathing tube or an airway stent. During surgery, a breathing tube or an airway stent, a support inside the airway, may be placed to make sure the airway stays open while healing occurs. If the breathing tube or stent moves out of its proper position, complications may happen. These can include an infection and a collapsed lung. Another complication called subcutaneous emphysema happens when air leaks into chest or neck tissue. These complications may need another surgery to correct them.

- Voice and swallowing problems. A sore throat or a raspy or breathy voice can happen after the endotracheal tube is removed or as a result of the surgery itself. Your surgeon and speech and language specialists can help manage speaking and swallowing problems that happen after surgery.

- Anesthesia side effects. Common side effects of anesthesia include sore throat, shivering, sleepiness, dry mouth, upset stomach and vomiting. These effects are usually short term but could continue for several days.

How you prepare

Carefully follow your healthcare team's directions about how to prepare for surgery.

Clothing and personal items

If your child is having surgery, favorite items from home such as a stuffed animal, blanket or photos put up in the hospital room may help comfort your child. This can help smooth the recovery.

Stop food and drink

Your healthcare team lets you know what time you or your child need to stop eating and drinking in the hours before surgery. Having food or drink before surgery could lead to complications during surgery, such as breathing food and liquid into the lungs. If you or your child eats or drinks after the requested cutoff time, surgery may have to be rescheduled.

What you can expect

Before the procedure

Laryngotracheal reconstruction surgery may be done using several different techniques:

- Endoscopy. In this method, instruments are passed through the mouth to reach the airway.

- Open-airway surgery. This involves making a cut in the neck to reach the airway.

Endoscopy and open-airway surgery may be done in one surgery, called a single-stage procedure, or in more than one surgery, known as a double-stage procedure.

Based on your or your child's condition and any other medical issues, the surgeon will talk with you about the best surgical plan.

Tests and exams before surgery

Several tests and exams are often needed before laryngotracheal reconstruction surgery. The goal of each test or exam is to help evaluate medical conditions that may cause problems with the airway or affect the surgical plan. The tests and exams also help to prepare for follow-up care that's needed.

- Endoscopic exam. This exam allows the surgeon to look at the airways. The surgeon can see the place, length and severity of the airway narrowing. Because acid reflux often occurs along with airway narrowing, the endoscopic exam may be combined with an upper endoscopy to look at the esophagus and stomach.

- Lung function tests. Also called pulmonary function tests, they measure the amount of air you can breathe in and out, and whether your lungs deliver enough oxygen to your blood. This can give information about how the lungs will do during some airway reconstruction procedures.

- CT scan and MRI. These imaging tests give detailed images of the structures of the larynx, trachea and lungs.

- Swallowing evaluations. Called dysphasia evaluations, these tests record the swallowing process during eating or drinking.

- Voice evaluation. This helps find the cause of vocal problems and helps plan effective treatment.

- pH/impedance probe studies. These studies help find out if acid and other liquid from the stomach are backing up into the esophagus and airway.

- Sleep study. Also called a polysomnogram, this test looks for changes in sleep caused by airway collapse.

Possible surgeries before airway reconstruction

One or more of the following surgeries may be needed before laryngotracheal reconstruction:

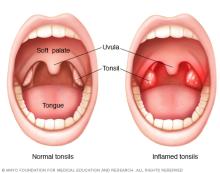

- Removing the adenoids or tonsils. Tonsils are the two round lumps of tissue that can be seen in the back of the throat. Adenoids are tiny glands higher in the throat behind the nose. Sometimes these tissues can become swollen and block the airway.

- Removing tissue in the larynx. This surgery may be needed to repair the larynx if it has partially collapsed. Any tissue blocking the airway is removed.

- Surgery to treat GERD. Sometimes, surgery for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) may be needed to help keep stomach acid from flowing back up into the esophagus. GERD can cause irritation and swelling of the airway.

During the procedure

Open-airway laryngotracheal reconstruction

Open-airway laryngotracheal reconstruction can be done in single or double stages, using different techniques. Placing cartilage grafts as part of the surgery is called a laryngotracheoplasty. The exact surgery depends on your or your child's condition.

Many people who have laryngotracheal reconstruction surgery already have a tracheostomy. This is a surgically placed tube that goes from the outside of the neck directly into the trachea to help with breathing.

During a single-stage reconstruction:

- A tracheostomy tube, if present, is removed.

- The surgeon widens the airway by placing precisely shaped pieces of flexible connective tissue called cartilage into the trachea. These small pieces of cartilage, called grafts, are taken from the ribs, ears, larynx or thyroid.

- A short-term tube is placed through the mouth or nose into the trachea. The tube is called an endotracheal tube. It supports the cartilage grafts. The endotracheal tube will usually stay in place from a few days to about two weeks. This depends on the amount of time it will take for the area to heal. The time it takes to heal depends on the amount and position of the cartilage grafts.

During a double-stage reconstruction:

- The surgeon widens the airway by placing precisely shaped pieces of cartilage into the trachea from the ribs, ears, larynx or thyroid.

- To keep the airway open long enough for it to heal, a tracheostomy tube is left in place and a hollow tube called a stent is placed in the trachea. The stent and tracheostomy tube stay in place until the area heals. Healing takes about 2 to 6 weeks or more. Sometimes a T-shaped hollow tube called a T tube replaces the tracheostomy tube during the healing process.

- The tracheostomy tube and stent are removed during a second surgery.

Hybrid option

A surgical option called a hybrid, or one-and-a-half-stage reconstruction, combines parts of both single-stage and double-stage reconstruction. With this technique, a single long stent is placed inside the trachea to support it. A smaller stent or tube is placed through an opening in the trachea to provide a safe airway for breathing during and after the surgery.

Other open-airway reconstruction options

Sometimes, the surgeon removes the narrow part of the windpipe completely. Then the surgeon sews the remaining ends of the trachea together.

Another surgical option is reshaping the narrow part of the trachea to make it wider. This is called a slide tracheoplasty.

Endoscopic laryngotracheal reconstruction

Endoscopic laryngotracheal reconstruction is a less invasive procedure. During endoscopic surgery, the surgeon puts a stiff viewing tube called a laryngoscope into the mouth. Surgical tools and a rod fitted with a light and camera are passed through the tube and into the airway to do the surgery. The surgery can be done without making any cuts in the skin or making only small cuts.

In some cases, the surgeon may use this method to place the cartilage grafts for laryngotracheoplasty. In some cases, the surgeon may be able to use lasers, balloons or other methods to open the narrowing without needing to do a laryngotracheoplasty.

Endoscopic laryngotracheal reconstruction may not be recommended if the airway is severely narrowed or scarred.

After the procedure

You or your child may need help from a breathing machine for a limited period of time. This is called mechanical ventilation. Sedation also may be needed to help prevent the breathing tube from coming out. How long sedation or help breathing is needed depends on other medical conditions and age.

Most people stay in the hospital 7 to 14 days after open-airway laryngotracheal reconstruction surgery, but it may be longer. Endoscopic surgery is sometimes done on an outpatient basis, so you or your child may go home the same day or spend several days in the hospital.

Results

Ongoing treatment and recovery after surgery varies depending on the procedure. Full recovery may take a few weeks to several months.

In the weeks after surgery, the surgeon does regular endoscopic exams in the office and operating room to check the airway healing. Speech therapy or other evaluations may be recommended to help with any voice or swallowing problems.

© 1998-2026 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research(MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use