Congenital mitral valve anomalies

Conditions

Overview

Congenital mitral valve anomalies are types of heart valve disease that are present at birth. That means they are congenital heart defects. The conditions affect the valve between the heart's upper and lower left chambers. That valve is called the mitral valve.

Mitral valve anomalies include:

- Thick or stiff valve flaps, also called leaflets.

- Leaflets that are joined, also called fused.

- Leaflets that are too long.

- Leaflets with spaces between them.

- Changes in the cords that support the valve. This might include missing cords, short and thick cords, or cords that are too long.

- More than one opening in the area of the mitral valve. This is called a double-orifice valve.

Types

Types of heart valve disease caused by mitral valve anomalies include:

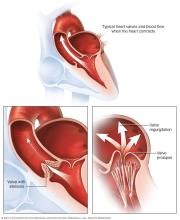

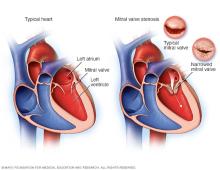

- Narrowing of the mitral valve, also called mitral valve stenosis. The valve flaps are stiff. The valve opening may be narrowed. Mitral valve stenosis reduces blood flow between the left heart chambers.

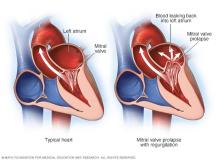

- Leaky mitral valve, also called mitral valve regurgitation. The valve flaps don't close tightly. Sometimes they push backward into the left upper heart chamber as the heart squeezes. As a result, the mitral valve leaks blood.

Some people have both mitral valve stenosis and mitral valve regurgitation.

Symptoms

Symptoms of congenital mitral valve anomalies may be serious or mild. Serious symptoms in babies and young children may include:

- Shortness of breath during feedings.

- Poor weight gain.

- A pale gray or bluish tint to the skin. Depending on skin color, these changes may be easier or harder to see.

- Heavy breathing.

- A fast heartbeat.

- Swelling in the legs, belly or around the eyes.

Sometimes, symptoms of congenital mitral valve anomalies don't appear until later in life, if at all. In older children and adults, symptoms may include:

- Trouble breathing, such as fast breathing or difficulty breathing during exercise.

- Chest pain or discomfort.

- Feeling very tired.

- Dizziness or fainting.

- Fast heartbeat or extra heartbeats

People with mitral valve anomalies also often have other heart conditions present at birth, which may cause other symptoms.

When to see a doctor

If you or your child has symptoms of heart valve disease, including congenital mitral valve anomalies, talk with a healthcare professional. You may be sent to a doctor trained in heart diseases, called a cardiologist.

Causes

The exact cause of congenital mitral valve anomalies is not known. The conditions happen when the unborn baby's heart does not grow the way it should during pregnancy. An unborn baby also is called a fetus.

Gene changes, certain medicines or health conditions, and environmental or lifestyle factors, such as smoking, may play a role.

Risk factors

Things that may raise the risk of congenital mitral valve anomalies include:

- Smoking. If you smoke, quit. Smoking during pregnancy or exposure to secondhand smoke can harm the hearts of unborn babies.

- Alcohol use. Drinking alcohol while pregnant is linked to a higher risk of heart conditions present at birth such as mitral valve anomalies.

- Some medicines. Taking some medicines during pregnancy may increase the risk of congenital heart defects. Examples of these medicines are lithium (Lithobid) for bipolar disorder and isotretinoin (Claravis, Myorisan, others), which is used to treat acne. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for high blood pressure also can increase your risk. Talk with your healthcare team about the medicines you take.

- Rubella, also called German measles. Having rubella during pregnancy can cause harmful changes in a baby's heart during pregnancy. A blood test done before pregnancy can determine whether you're immune to rubella. A vaccine is available for those who aren't immune.

- Diabetes. Careful control of blood sugar before and during pregnancy can reduce the risk of heart conditions in the baby. Diabetes that develops during pregnancy is called gestational diabetes. It generally doesn't increase a baby's risk of congenital heart defects.

Diagnosis

To diagnose congenital mitral valve anomalies, a healthcare professional does a physical exam and listens to the heart and lungs. A sound called a heart murmur may be heard.

A member of your healthcare team asks questions about the symptoms and medical and family history.

Tests

Imaging tests are done to diagnose congenital mitral valve anomalies.

An echocardiogram is the main test used to diagnose the condition. The test also is called a heart ultrasound. It uses sound waves to make pictures of the beating heart. An echocardiogram can show the structure of the heart and heart valves and blood flow through the heart.

There are different types of echocardiograms. The type done depends on the information the healthcare professional needs.

- Transthoracic echocardiogram. This is a standard echocardiogram test. It takes pictures of the heart from outside the body. The healthcare professional presses an ultrasound device firmly against the skin. Sound waves from the device go through the chest to the heart. The device records the sound wave echoes from the heart. A computer changes them into moving images.

- Fetal echocardiogram. This type of transthoracic echocardiogram is done during pregnancy to check the baby's heart. The ultrasound wand is moved over the pregnant person's belly.

- Transesophageal echocardiogram. This test takes pictures of the heart from inside the body. It may be done if the healthcare professional needs more information about the heart. During this test, the healthcare professional guides a thin tube called a catheter down the throat and into the esophagus close to the heart. The ultrasound device goes through the tube and moves near the heart.

Other tests, such as a chest X-ray or electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG), also may be done.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the symptoms and how severe they are.

Surgeries or other procedures

Some people with congenital mitral anomalies may need surgery to repair or replace the mitral valve.

Mitral valve repair

Mitral valve repair is done when possible, as it saves the heart valve. Surgeons may do one or more of the following during mitral valve repair:

- Patch holes in a valve.

- Reconnect valve flaps.

- Separate valve flaps that have fused.

- Separate, remove or reshape muscle near the valve.

- Separate, shorten, lengthen or replace the cords that support the valve.

- Remove excess valve tissue so that the leaflets can close tightly.

- Tighten or reinforce the ring around a valve, called the annulus, using sutures or an artificial ring.

Mitral valve replacement

If the mitral valve can't be repaired, the valve may need to be replaced. In mitral valve replacement, a surgeon removes the damaged valve. It's replaced with a mechanical valve or a tissue valve made from cow, pig or human heart tissue. The tissue valve also is called a biological tissue valve.

Biological tissue valves wear down over time. They eventually need to be replaced. While mechanical valves last longer, they do not last forever — especially in children. If you have a mechanical valve, you need blood thinners for life to prevent blood clots. Talk with your healthcare professional about the benefits and risks of each type of valve. The specific valve used is chosen by the cardiologist, surgeon and family after evaluating the risks and benefits.

Sometimes, people need another valve repair or surgery to replace a valve that no longer works.

Follow-up care

People born with congenital mitral valve anomalies need lifelong health checkups. It's best to be cared for by a healthcare professional trained in congenital heart conditions. These types of doctors are called pediatric and adult congenital cardiologists.

© 1998-2026 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research(MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use