Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

Conditions

Overview

Creutzfeldt-Jakob (KROITS-felt YAH-kobe) disease, also known as CJD, is a rare brain disorder that leads to dementia. It belongs to a group of human and animal diseases known as prion disorders. Symptoms of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease can be similar to those of Alzheimer's disease. But Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease usually gets worse much faster and leads to death.

CJD received public attention in the 1990s when some people in the United Kingdom became sick with a form of the disease. They developed variant CJ, known as vCJD, after eating meat from diseased cattle. However, most cases of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease haven't been linked to eating beef.

All types of CJD are serious but are very rare. About 1 to 2 cases of CJD are diagnosed per million people around the world each year. The disease most often affects older adults.

Symptoms

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is marked by changes in mental abilities. Symptoms get worse quickly, usually within several weeks to a few months. Early symptoms include:

- Personality changes.

- Memory loss.

- Impaired thinking.

- Blurry vision or blindness.

- Insomnia.

- Problems with coordination.

- Trouble speaking.

- Trouble swallowing.

- Sudden, jerky movements.

Death usually occurs within a year. People with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease usually die of medical issues associated with the disease. They might include having trouble swallowing, falls, heart issues, lung failure, or pneumonia or other infections.

In people with variant CJD, changes in mental abilities may be more apparent in the beginning of the disease. In many cases, dementia develops later in the illness. Symptoms of dementia include the loss of the ability to think, reason and remember.

Variant CJD affects people at a younger age than CJD. Variant CJD appears to last 12 to 14 months.

Another rare form of prion disease is called variably protease-sensitive prionopathy (VPSPr). It can mimic other forms of dementia. It causes changes in mental abilities and problems with speech and thinking. The course of the disease is longer than other prion diseases — about 24 months.

Causes

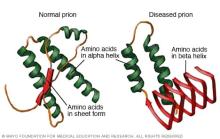

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and related conditions appear to be caused by changes to a type of protein called a prion. These proteins are typically produced in the body. But when they encounter infectious prions, they fold and become another shape that's not typical. They can spread and affect processes in the body.

How Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease develops

The risk of getting CJD is low. The disease can't be spread through coughing or sneezing. It also can't be spread by touching or sexual contact. CJD can develop in three ways:

- Sporadically. Most people with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease develop the disease for no apparent reason. This type, called spontaneous CJD or sporadic CJD, accounts for most cases.

-

By inheritance. Fewer than 15% of people with CJD have a family history. They may test positive for genetic changes associated with the disease. This type is referred to as familial CJD.

Changes in a gene called PRNP that makes prion protein cause the genetic forms of the disease. Rare genetic forms also include Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker syndrome. This syndrome causes problems with movement and cognition. It often affects people in their 40s. Another rare genetic form includes fatal familial insomnia. This causes an inability to sleep and changes in memory and thinking.

-

By contamination. A small number of people have developed CJD as a result of medical procedures. These procedures included injections of pituitary human growth hormone from an infected source. They also included cornea and skin transplants from people who had CJD. Medical centers have changed their procedures to eliminate these risks.

Also, a few people have developed Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease after brain surgery with contaminated instruments. This happened because standard cleaning methods don't destroy the prions that cause the disease. Today instruments that may have been contaminated with CJD are destroyed.

Cases related to medical procedures are referred to as iatrogenic CJD.

A small number of people have developed variant CJD from eating contaminated beef. Variant CJD is linked to eating beef from cattle infected with mad cow disease. Mad cow disease is known as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE).

Risk factors

Most cases of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease occur for unknown reasons. So risk factors can't be identified. But a few factors seem to be associated with different kinds of CJD.

- Age. Sporadic CJD tends to develop later in life, usually around age 60. Onset of familial CJD occurs slightly earlier. And vCJD has affected people at a much younger age, usually in their late 20s.

- Genetics. People with familial CJD have genetic changes that cause the disease. To develop this form of the disease, a child must have one copy of the gene that causes CJD. The gene can be passed down from either parent. If you have the gene, the chance of passing it on to your children is 50%.

Exposure to contaminated tissue. People who've received infected human growth hormone may be at risk of iatrogenic CJD. Receiving a transplant of tissue that covers the brain, called dura mater, from someone with CJD also can put a person at risk of iatrogenic CJD.

The risk of getting vCJD from eating contaminated beef is very low. In countries that have implemented effective public health measures, the risk is virtually nonexistent. Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a prion disease that affects deer, elk, reindeer and moose. It has been found in some areas of North America. To date, no documented cases of CWD have caused disease in humans.

Complications

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease has serious effects on the brain and body. The disease usually progresses quickly. Over time, people with CJD withdraw from friends and family. They also lose the ability to care for themselves. Many slip into a coma. The disease is always fatal.

Prevention

There's no known way to prevent sporadic CJD. If you have a family history of neurological disease, you may benefit from talking with a genetics counselor. A counselor can help you sort through your risks.

Preventing Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease related to medical procedures

Hospitals and other medical institutions follow clear policies to prevent CJD related to medical procedures, known as iatrogenic CJD. These measures have included:

- Using only human-made human growth hormone. This is used instead of taking the hormone from human pituitary glands.

- Destroying surgical instruments that may have been exposed to CJD. This includes instruments used in procedures that involve the brain or nervous tissue of someone with known or suspected Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

- Single-use kits for spinal taps, also known as lumbar punctures.

To help ensure the safety of the blood supply, people with a risk of exposure to CJD or vCJD aren't eligible to donate blood in the United States. This includes people who:

- Have a blood relative who has been diagnosed with familial CJD. Blood relatives include parents, aunts, uncles, grandparents and cousins.

- Have received a dura mater brain graft. Dura mater is the tissue that covers the brain.

- Have received human growth hormone from cadavers.

The United Kingdom (U.K.) and certain other countries also have specific restrictions regarding blood donations from people with a risk of exposure to CJD or vCJD.

Preventing variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

The risk of getting vCJD in the United States remains very low. Only four cases have been reported in the U.S. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), strong evidence suggests that these cases were acquired in other countries outside of the U.S.

In the United Kingdom (U.K.), where the majority of vCJD cases have occurred, fewer than 200 cases have been reported. CJD incidence peaked in the U.K. between 1999 and 2000 and has been declining since. A very small number of other vCJD cases also have been reported in other countries worldwide.

To date, there is no evidence that people can develop Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease from consuming the meat of animals infected with chronic wasting disease (CWD). However, the CDC recommends that hunters strongly consider taking precautions. The CDC recommends having deer and elk tested before eating the meat in areas where CWD is known to be present. Hunters also should avoid shooting or handling meat from deer or elk that appear sick or are found dead.

Regulating potential sources of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

Most countries have taken steps to prevent meat infected with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) from entering the food supply. Steps include:

- Tight restrictions on importing cattle from countries where BSE is common.

- Restrictions on animal feed.

- Strict procedures for dealing with sick animals.

- Surveillance and testing methods for tracking cattle health.

- Restrictions on which parts of cattle can be processed for food.

Diagnosis

A brain biopsy or an exam of brain tissue after death, known as an autopsy, is the gold standard to confirm the presence of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, known as CJD. But health care providers often can make an accurate diagnosis before death. They base a diagnosis on your medical and personal history, a neurological exam, and certain diagnostic tests.

A neurological exam may point to CJD if you're experiencing:

- Muscle twitching and spasms.

- Changes in reflexes.

- Coordination problems.

- Vision problems.

- Blindness.

In addition, health care providers commonly use these tests to help detect CJD:

- Electroencephalogram, also known as an EEG. This test measures the brain's electrical activity. It's done by placing small metal discs called electrodes on the scalp. EEG results of people with CJD and variant CJD show a pattern that's not typical.

- MRI. This imaging uses radio waves and a magnetic field to create detailed images of the head and body. MRI is especially useful in looking for brain disorders. MRI creates high-resolution images. People with CJD have characteristic changes that can be detected on certain MRI scans.

Spinal fluid tests. Spinal fluid surrounds and cushions the brain and spinal cord. In a test called a lumbar puncture, also known as a spinal tap, a small amount of spinal fluid is taken for testing. This test can rule out other diseases that cause similar symptoms to CJD. It also can detect levels of proteins that may point to CJD or vCJD.

A newer test called real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC) can detect the presence of the prion proteins that cause CJD. This test can diagnose CJD before death, unlike an autopsy.

Treatment

No effective treatment exists for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease or any of its variants. Many medicines have been tested and haven't shown benefits. Health care providers focus on relieving pain and other symptoms and on making people with these diseases as comfortable as possible.

Preparing for your appointment

You're likely to start by seeing your primary care provider. In some cases when you call for an appointment, you may be referred immediately to a brain specialist, known as a neurologist.

Here's some information to help you prepare for your appointment.

What you can do

- List your symptoms, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for which you scheduled the appointment.

- Write down key personal information, including recent life changes.

- List medicines, vitamins and supplements you take.

- Bring a family member or friend along, if possible. A family member or friend might help you remember something you missed or forgot.

- Write down questions to ask your health care provider.

For Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, some basic questions to ask your provider include:

- What is likely causing my symptoms?

- Other than the most likely cause, what are other possible causes for my symptoms?

- What tests do I need?

- What is the best course of action?

- Are there restrictions I need to follow?

- Should I see a specialist?

- I have other medical conditions. How do I manage them together?

- Are there brochures or other printed materials I can have? What websites do you recommend?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care provider is likely to ask you a number of questions, including:

- When did your symptoms begin?

- Have your symptoms been continuous or occasional?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your symptoms?

- Has anyone in your family had Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease?

- Have you lived or traveled extensively outside the United States?

© 1998-2026 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research(MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use