Enlarged spleen (splenomegaly)

Conditions

Overview

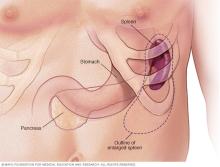

Your spleen is an organ that sits just below your left rib cage. Many conditions — including infections, liver disease and some cancers — can cause an enlarged spleen. An enlarged spleen is also known as splenomegaly (spleh-no-MEG-uh-lee).

An enlarged spleen usually doesn't cause symptoms. It's often discovered during a routine physical exam. A doctor usually can't feel the spleen in an adult unless it's enlarged. Imaging and blood tests can help identify the cause of an enlarged spleen.

Treatment for an enlarged spleen depends on what's causing it. Surgery to remove an enlarged spleen usually isn't needed, but sometimes it's recommended.

Symptoms

An enlarged spleen typically causes no signs or symptoms, but sometimes it causes:

- Pain or fullness in the left upper belly that can spread to the left shoulder

- A feeling of fullness without eating or after eating a small amount because the spleen is pressing on your stomach

- Low red blood cells (anemia)

- Frequent infections

- Bleeding easily

When to see a doctor

See your doctor promptly if you have pain in your left upper belly, especially if it's severe or the pain gets worse when you take a deep breath.

Causes

A number of infections and diseases can cause an enlarged spleen. The enlargement might be temporary, depending on treatment. Contributing factors include:

- Viral infections, such as mononucleosis

- Bacterial infections, such as syphilis or an infection of your heart's inner lining (endocarditis)

- Parasitic infections, such as malaria

- Cirrhosis and other diseases affecting the liver

- Various types of hemolytic anemia — a condition characterized by early destruction of red blood cells

- Blood cancers, such as leukemia and myeloproliferative neoplasms, and lymphomas, such as Hodgkin's disease

- Metabolic disorders, such as Gaucher disease and Niemann-Pick disease

- Pressure on the veins in the spleen or liver or a blood clot in these veins

- Autoimmune conditions, such as lupus or sarcoidosis

How the spleen works

Your spleen is tucked below your rib cage next to your stomach on the left side of your belly. Its size generally relates to your height, weight and sex.

This soft, spongy organ performs several critical jobs, such as:

- Filtering out and destroying old, damaged blood cells

- Preventing infection by producing white blood cells (lymphocytes) and acting as a first line of defense against disease-causing organisms

- Storing red blood cells and platelets, which help your blood clot

An enlarged spleen affects each of these jobs. When it's enlarged, your spleen may not function as usual.

Risk factors

Anyone can develop an enlarged spleen at any age, but certain groups are at higher risk, including:

- Children and young adults with infections, such as mononucleosis

- People who have Gaucher disease, Niemann-Pick disease, and several other inherited metabolic disorders affecting the liver and spleen

- People who live in or travel to areas where malaria is common

Complications

Potential complications of an enlarged spleen are:

- Infection. An enlarged spleen can reduce the number of healthy red blood cells, platelets and white cells in your bloodstream, leading to more frequent infections. Anemia and increased bleeding also are possible.

- Ruptured spleen. Even healthy spleens are soft and easily damaged, especially in car crashes. The possibility of rupture is much greater when your spleen is enlarged. A ruptured spleen can cause life-threatening bleeding in your belly.

Diagnosis

An enlarged spleen is usually detected during a physical exam. Your doctor can often feel it by gently examining your left upper belly. However, in some people — especially those who are slender — a healthy, normal-sized spleen can sometimes be felt during an exam.

Your doctor might order these tests to confirm the diagnosis of an enlarged spleen:

- Blood tests, such as a complete blood count to check the number of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets in your system and liver function

- Ultrasound or CT scan to help determine the size of your spleen and whether it's crowding other organs

- MRI to trace blood flow through the spleen

Finding the cause

Sometimes more testing is needed to find the cause of an enlarged spleen, including a bone marrow biopsy exam.

A sample of solid bone marrow may be removed in a procedure called a bone marrow biopsy. Or you might have a bone marrow aspiration, which removes the liquid portion of your marrow. Both procedures might be done at the same time.

Liquid and solid bone marrow samples are usually taken from the pelvis. A needle is inserted into the bone through an incision. You'll receive either a general or a local anesthetic before the test to ease discomfort.

A needle biopsy of the spleen is rare because of the risk of bleeding.

Your doctor might recommend surgery to remove your spleen (splenectomy) for diagnostic purposes when there's no identifiable cause for the enlargement. More often, the spleen is removed as treatment. After surgery to remove it, the spleen is examined under a microscope to check for possible lymphoma of the spleen.

Treatment

Treatment for an enlarged spleen focuses on the what's causing it. For example, if you have a bacterial infection, treatment will include antibiotics.

Watchful waiting

If you have an enlarged spleen but don't have symptoms and the cause can't be found, your doctor might suggest watchful waiting. You see your doctor for reevaluation in 6 to 12 months or sooner if you develop symptoms.

Spleen removal surgery

If an enlarged spleen causes serious complications or the cause can't be identified or treated, surgery to remove your spleen (splenectomy) might be an option. In chronic or critical cases, surgery might offer the best hope for recovery.

Elective spleen removal requires careful consideration. You can live an active life without a spleen, but you're more likely to get serious or even life-threatening infections after spleen removal.

Reducing infection risk after surgery

After spleen removal, certain steps can help reduce your risk of infection, including:

- A series of vaccinations before and after the splenectomy. These include the pneumococcal (Pneumovax 23), meningococcal and haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccines, which protect against pneumonia, meningitis and infections of the blood, bones and joints. You'll also need the pneumococcal vaccine every five years after surgery.

- Taking penicillin or other antibiotics after your surgery and anytime you or your doctor suspects the possibility of an infection.

- Calling your doctor at the first sign of a fever, which could indicate an infection.

- Avoiding travel to parts of the world where certain diseases, such as malaria, are common.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Avoid contact sports — such as soccer, football and hockey — and limit other activities as recommended to reduce the risk of a ruptured spleen.

It's also important to wear a seat belt. If you're in a car accident, a seat belt can help protect your spleen.

Finally, be sure to keep your vaccinations up to date because your risk of infection is increased. That means at least an annual flu shot, and a tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis booster every 10 years. Ask your doctor if you need other vaccines.

© 1998-2026 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research(MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use