Bladder removal surgery (cystectomy)

Procedures

Overview

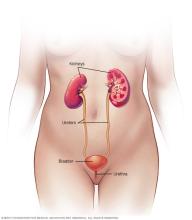

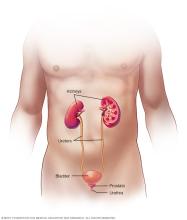

Cystectomy (sis-TEK-tuh-me) is a surgery to remove the urinary bladder.

Removing the whole bladder is called a radical cystectomy. This most often includes removal of the prostate and seminal vesicles or the uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes and part of the vagina.

After removing the bladder, a surgeon also needs to make a new way for the body to store urine and for urine to leave the body. This is called urinary diversion. A surgeon talks about the choices for urinary diversion that may be right for you.

A radical cystectomy treats cancer that has grown into muscle tissue of the bladder or a bladder cancer that comes back. A partial cystectomy, although rarely done, removes a cancerous tumor in one part of the bladder. Removing only the bladder, called a simple cystectomy, may treat conditions that aren't cancer, called benign.

Why it's done

You may need bladder removal surgery, also called cystectomy, to treat:

- Cancer that begins in or spreads to the bladder.

- Issues with the urinary system present at birth.

- Conditions of the nervous system, called neurological conditions, or inflammatory conditions that affect the urinary system.

- Complications from treatments for other cancers, such as radiation, that cause issues with the bladder.

The type of cystectomy and new storage that you have depends on many things. These include the reason for surgery, your overall health, what you want and your care needs.

Risks

Cystectomy is a complex surgery. Cystectomy risks include:

- Bleeding.

- Blood clots.

- Infection.

- Poor wound healing.

- Damage to nearby organs or tissues.

- Organ damage due to the body reacting poorly to infection, called sepsis.

- Rarely, death linked to complications from surgery.

Other risks linked to urinary diversion depend on the procedure. Complications may include:

- Ongoing diarrhea.

- Decline in kidney function.

- Imbalance in needed minerals.

- Not enough vitamin B-12.

- Urinary tract infections.

- Kidney stones.

- Loss of bladder control, called urinary incontinence.

- A blockage that keeps food or liquid from passing through the intestines, called a bowel obstruction.

- A blockage in one of the tubes that carries urine from the kidneys, called ureter blockage.

Some complications may be life-threatening or lead to being in the hospital. Some people may need another surgery to correct problems. Your surgical team tells you when to call your care team or when to go to the emergency room during your recovery.

How you prepare

Before your cystectomy, you talk to your surgeon, your anesthesiologist and other members of the care team about your health and any factors that may affect the surgery. These factors may include:

- Long-term medical conditions.

- Other surgeries you've had.

- Medicine allergies.

- Earlier reactions to anesthesia.

- Stops in breathing during sleep, called obstructive sleep apnea.

Also review with the surgical team your use of the following:

- All the medicines you take.

- Vitamins, herbal medicines or other dietary supplements.

- Alcohol.

- Cigarettes.

- Illicit drugs.

- Caffeine.

If you smoke, talk to a member of your healthcare team about what help you need to quit. Smoking can affect your recovery from surgery and can cause problems with the medicine used to put you to sleep, called anesthesia.

Diet and medicines before surgery

Your surgeon may ask you to have a clear liquid diet for 1 to 2 days before surgery. You likely need to stop eating and drinking after midnight on the night before your procedure. Your healthcare team will tell you what medicines to stop taking in the days before surgery.

Urinary diversion procedure

With urinary diversion, you get a new way for urine to be stored in and leave your body after the bladder is removed. The goals of urinary diversion are to let your body make and store urine safely.

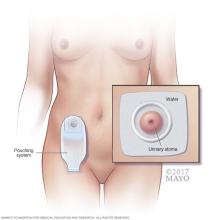

Some types of urinary diversions let you urinate when you want or need to. With other types, urine drains on its own into a bag that sits on the belly. Your care team wants to help you have the best quality of life you can after surgery. They will talk to you about your choices and help you decide which is best.

Devices used for urinary diversion depend on the type of surgery. Devices may include tubes or bags to collect urine. These devices need to be used and cleaned correctly. A member of your care team trains you how to use and care for these devices. This will help you or a care provider be ready to take on this role after your surgery.

What you can expect

Choices for cystectomy surgery include:

- Open surgery. This approach uses a single cut, called an incision, on the belly to get to the pelvis and bladder.

- Minimally invasive surgery. With minimally invasive surgery, the surgeon makes several small cuts in the belly. The surgeon then puts in special surgical tools through the cuts to work on the bladder. This type of surgery also is called laparoscopic surgery.

- Robotic surgery. Robotic surgery is a type of minimally invasive surgery. The surgeon sits at a console and moves robotic surgical tools.

During the procedure

You're given a medicine, called general anesthesia, that keeps you asleep during surgery. Once you're asleep, your surgeon cuts into your belly. There's one large cut for open surgery or several smaller cuts for minimally invasive or robotic surgery.

Your surgeon removes the bladder from surrounding tissues. If the treatment is for bladder cancer, the surgeon also will remove nearby lymph nodes. The lymph nodes are part of the immune system. These will be looked at in a lab to see if cancer has spread to them.

A radical cystectomy includes removal of the prostate and seminal vesicles or removal of the uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes and sometimes part of the vagina. How much of the urethra is kept depends on the type of urinary diversion the surgeon makes.

After your bladder is removed, your surgeon makes a new system for removing urine, called a urinary diversion. Choices include:

-

Ileal conduit. The surgeon uses a piece of the small intestine to make a tube, called a conduit. The ureters, which were joined to the bladder, are then joined to the conduit.

Urine drains into the conduit and passes outside the body through a hole in the wall of the belly, called a stoma. The urine collects in a pouch worn under clothes. The pouch needs to be drained often and replaced regularly.

- Continent urinary reservoir. During this procedure, the surgeon uses a piece of the intestines to make a pouch, called a reservoir, inside the belly. Like the ileal conduit, the reservoir joins to ureters and a stoma in the belly wall. But the reservoir stores the urine. To drain it, you put a thin tube, called a catheter, into the stoma through a small opening in the belly.

- Neobladder reconstruction. The surgeon reshapes a part of the intestines into a pouch that serves as a bladder. The new bladder goes into the same place as the old bladder and joins to the ureters and urethra. The neobladder allows you to urinate as you did with your old bladder. You may need to put a catheter into your urethra to drain the new bladder all the way.

After the procedure

After general anesthesia, you may have side effects such as sore throat, shivering, sleepiness, dry mouth, nausea and vomiting. You may get medicines to ease symptoms.

Starting the morning after surgery, your healthcare team may have you get up and walk often. Walking promotes healing and helps the bowel work again. It also improves blood flow and helps prevent joint stiffness and blood clots.

The slow return of the bowel working often delays recovery after a radical cystectomy. If you have an open procedure, you'll likely be in the hospital for 5 to 7 days. With a minimally invasive procedure, your time in the hospital may be shorter.

Before you leave the hospital, a nurse or other healthcare professional gives you written instructions about wound care and guidelines for when to call your care team or get urgent care. Depending on the type of urinary diversion you had, you'll also get instructions about care, cleaning and use of devices.

Follow-up appointments

You return to the clinic for follow-up care in the first few weeks after the cystectomy and again after a few months. At these appointments, your healthcare team will check to make sure that your upper urinary tract drains well and that the water and sodium, called electrolytes, in your body are balanced.

After bladder removal surgery, you have follow-up appointments for the rest of your life. These are to check that the neobladder or other urinary diversion is working right. If you have a cystectomy to treat bladder cancer, you have regular follow-up visits to check for cancer returning.

Return to activities

During the first six weeks or so after surgery, you may need to restrict activities such as lifting, driving, bathing, and going back to work or school. You should be able to shower soon after surgery.

Results

A cystectomy and urinary diversion can help lengthen life. But these surgeries do cause lifelong changes in both how your urinary system works and your sex life. These changes can affect your quality of life.

With time and support, you can learn to manage these changes. Ask your healthcare team if there are resources or support groups that may help you.

Urine voiding

A neobladder works much like your old bladder. But it may take some time for the neobladder to work well. Right after surgery, you may have trouble controlling your bladder, called urinary incontinence. This may happen until the neobladder gets bigger and the muscles that support it get stronger.

It helps to keep a regular schedule to urinate. You may need to pass a tube called a catheter through the urethra to fully drain your bladder.

If you have a stoma, proper care of the stoma helps avoid complications. You need to empty a urine-collecting bag or use a catheter through the stoma several times a day. You also need to follow instructions for taking care of and getting rid of devices.

Your care team can offer support and answer questions.

Sexual activity

A cystectomy and urinary diversion often affect sexual activity. Your healthcare professional or a sexual health specialist can help.

For women, the removal of some vaginal tissue during surgery can make sexual stimulation or intercourse after surgery uncomfortable. Nerve damage also can affect arousal and having an orgasm.

For men, nerve damage during surgery can affect being able to have erections. Removal of the seminal vesicles and the prostate means not being able to ejaculate. While men still may be able to have orgasms, no fluid will come out.

You may feel uncomfortable about being close to a partner because of a stoma or wearing a pouch. To help prevent leaks, empty the pouch before sex. A pouch cover, sash or snug-fitting top can secure the pouch and keep it out of your way. You may want to try different sexual activities or positions to find what is comfortable for you.

© 1998-2026 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research(MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use