Tracheostomy

Procedures

Overview

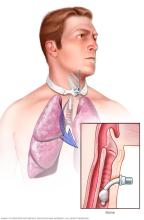

A tracheostomy (tray-key-OS-tuh-me) is a hole that surgeons make through the front of the neck and into the windpipe, also known as the trachea. Surgeons place a tracheostomy tube into the hole to keep it open for breathing. The term for the surgical procedure to create this opening is tracheotomy.

A tracheostomy allows air to pass into the windpipe to help with breathing. Tracheotomy is done when the usual way of breathing is blocked or reduced. A tracheostomy is often needed when health problems require long-term use of a machine called a ventilator to help with breathing. A tracheostomy also may be needed when surgery would require breathing to be rerouted for a short time because of swelling or airway blockage in the neck or face. Rarely, an emergency tracheotomy is done when the airway is suddenly blocked, such as after a major injury to the face or neck.

When a tracheostomy is no longer needed, it's allowed to heal shut, or a surgeon can close it. For some people, tracheostomies stay in place for the rest of their lives.

Why it's done

A tracheostomy may be needed when:

- Medical conditions make the use of a breathing machine, also known as a ventilator, necessary for an extended period, usually more than one or two weeks.

- Medical conditions, such as vocal cord paralysis, throat cancer or mouth cancer, block or narrow the airway.

- Paralysis, conditions that affect the brain and nerves, or other conditions make it hard to cough up mucus from your throat and make direct suctioning of the windpipe, also known as your trachea, necessary to clear your airway.

- Major head or neck surgery is planned. A tracheostomy helps with breathing during recovery.

- Severe injury to the head or neck blocks the usual way of breathing.

- Other emergency situations occur that block your ability to breathe and emergency personnel can't put a breathing tube through your mouth and into your windpipe.

Emergency care

Most tracheotomies are done in a hospital setting. But in an emergency, emergency personnel may need to create a hole in a person's throat when outside of a hospital, such as at an accident scene.

Emergency tracheotomies are hard to do and have a greater risk of complications than those that are planned. A related and somewhat less risky — and more straightforward — procedure used in emergency care is a cricothyrotomy (kry-koe-thie-ROT-uh-me). This procedure creates a hole slightly higher up in the neck right below the voice box, also known as the larynx. The hole is placed right below the Adam's apple, which usually looks like a bump on the throat and is made up of thyroid cartilage that covers the front of the voice box.

Once a person transfers to a hospital and is stable, a tracheotomy replaces a cricothyrotomy if that person needs help breathing long term.

Risks

Tracheostomies are generally safe, but they have risks. Some complications are more likely during or shortly after surgery. The risk of complications is greater when a tracheotomy is done as an emergency procedure.

Complications that can occur right away include:

- Bleeding.

- Damage to the windpipe, thyroid gland or nerves in the neck.

- Movement of the tracheostomy tube or placement of the tube that isn't correct.

- The trapping of air in tissue under the skin of the neck. This is known as a subcutaneous emphysema. This issue can cause breathing problems and damage to the windpipe or the food pipe, also known as the esophagus.

- Buildup of air between the chest wall and lungs that causes pain, breathing problems or lung collapse. This is known as pneumothorax.

- A collection of blood, also known as a hematoma, that may form in the neck and squeeze the windpipe, causing breathing problems.

Long-term complications are more likely the longer a tracheostomy is in place. These problems include:

- Blockage of the tracheostomy tube.

- Movement of the tracheostomy tube from the windpipe.

- Damage, scarring or narrowing of the windpipe.

- Development of an unusual passage between the windpipe and the esophagus. This makes it more likely that fluids or food could enter the lungs.

- Development of a passage between the windpipe and the large artery that supplies blood to the right arm and right side of the head and neck. This can result in life-threatening bleeding.

- Infection around the tracheostomy or infection in the windpipe and bronchial tubes or lungs. An infection in the windpipe and bronchial tubes is known as tracheobronchitis. An infection in the lungs is known as pneumonia.

If you still need a tracheostomy after you've left the hospital, you'll likely need to keep regularly scheduled appointments to watch for possible complications. You'll also likely get instructions about when you should call your healthcare professional about problems, such as:

- Bleeding at the tracheostomy site or from the windpipe.

- Having a hard time breathing through the tube.

- Pain or a change in comfort level.

- A change in skin color or swelling around the tracheostomy.

- A change in the position of the tracheostomy tube.

How you prepare

How you prepare for a tracheostomy depends on the type of procedure you'll have. If you'll be having general anesthesia, your healthcare professional may ask that you not eat or drink for several hours before your procedure. You also may be asked to stop taking certain medicines.

Plan for your hospital stay

After the tracheostomy procedure, you'll likely stay in the hospital for several days as your body heals. If your tracheostomy is a planned procedure, you can prepare for your hospital stay by bringing:

- Comfortable clothing, such as pajamas, a robe and slippers.

- Personal care items, such as your toothbrush and shaving supplies.

- Entertainment to help you pass the time, such as books, magazines or games.

- A communication method, such as a pencil and a pad of paper, a smartphone, or a computer, as you won't be able to talk at first. Your healthcare team may give you a writing whiteboard with a marker after your tracheostomy to help you communicate during the early part of your recovery.

What you can expect

During the procedure

A tracheotomy is most commonly done in an operating room with general anesthetic, which is medicine that puts you to sleep. Occasionally, the procedure needs to be done when you're awake or lightly sedated rather than fully asleep. To do this, a surgeon uses a local anesthetic to numb the neck and throat to complete the procedure comfortably. Once the tracheostomy is completed and a tube is in place, you can then be safely put under general anesthesia to complete other parts of surgery if needed.

The type of procedure you have depends on why you need a tracheostomy and whether the procedure was planned. There are basically two options:

- Surgical tracheotomy. A surgeon can do this procedure in an operating room or in a hospital room. The surgeon usually makes a horizontal cut through the skin at the lower part of the front of your neck. The surgeon pulls back the surrounding muscles, and a small portion of the thyroid gland is cut. This exposes the windpipe, also known as the trachea. At a specific spot on your windpipe near the base of your neck, the surgeon creates a tracheostomy hole.

- Minimally invasive tracheotomy. Also called a percutaneous tracheotomy, a surgeon usually does this procedure in a hospital room. The surgeon makes a small cut near the base of the front of the neck. A special lens is fed through the mouth so that the surgeon can view the inside of the throat. Using this view of the throat, the surgeon guides a needle into the windpipe to create the tracheostomy hole. Then the surgeon expands the hole to the right size for the tube.

For both procedures, the surgeon inserts a tracheostomy tube into the hole. A neck strap attached to the faceplate of the tube keeps it from slipping out of the hole. Temporary sutures also can secure the faceplate to your neck.

After the procedure

You'll likely spend several days in the hospital as your body heals. During that time, you learn the skills you need to maintain and cope with your tracheostomy, including how to:

- Care for your tracheostomy tube. A nurse teaches you how to clean and change your tracheostomy tube to help prevent infection and lower the risk of complications. You continue to do this as long as you have a tracheostomy.

- Speak. Generally, a tracheostomy prevents speaking because air goes out the tracheostomy rather than up through your voice box. But there are devices and techniques to redirect airflow enough to allow you to speak. Depending on the type of tube, width of your windpipe and condition of your voice box, you may be able to speak with the tube in place. If needed, a speech therapist or a nurse trained in tracheostomy care can help you learn to use your voice again.

- Eat. While you're healing, swallowing will likely be hard. You'll get nutrients through an IV, a feeding tube that passes through your mouth or nose, or a tube inserted directly into your stomach. When you're ready to eat again, you may need to work with a speech therapist. The speech therapist can help you regain the muscle strength and coordination you need to swallow.

- Cope with dry air. The air you breathe will be much drier because it no longer passes through your moist nose, mouth and throat before reaching your lungs. This can cause irritation, coughing and too much mucus coming out of the tracheostomy. Putting small amounts of saline directly into the tracheostomy tube, as directed, may help loosen mucus. Or a saline nebulizer treatment may help. A device called a heat and moisture exchanger captures moisture from the air you exhale and humidifies the air you inhale. A humidifier or vaporizer adds moisture to the air in a room.

- Manage other effects. Your healthcare team shows you ways to care for other common effects of a tracheostomy. For example, you may learn to use a suction machine to help you clear mucus from your throat or airway.

Results

In most cases, a tracheostomy is needed for a short time as a breathing route until other medical issues resolve. If you don't know how long you may need to be connected to a ventilator, the tracheostomy is often the best permanent solution.

Your healthcare team talks with you to help decide when it's the right time to take out the tracheostomy tube. The hole may close and heal on its own, or a surgeon can close it.

© 1998-2026 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research(MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use