Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

Conditions

Overview

Mild cognitive impairment is the in-between stage between typical thinking skills and dementia. The condition causes memory loss and trouble with language and judgment, but it doesn't affect daily activities.

People with mild cognitive impairment, also known as MCI, may be aware that their memory or mental ability has changed. Family and close friends also may notice changes. But these changes aren't bad enough to impact daily life or affect usual activities.

MCI raises the risk of developing dementia caused by Alzheimer's disease or other brain conditions. But for some people with mild cognitive impairment, symptoms might never get worse or even get better.

Symptoms

Symptoms of mild cognitive impairment, also known as MCI, include trouble with memory, language and judgment. The symptoms are more serious than the memory issues that are expected as people get older. But the symptoms don't affect daily life at work or at home.

The brain, like the rest of the body, changes with age. Many people notice they become more forgetful as they age. It may take longer to think of a word or to recall a person's name. But if concerns with memory go beyond what's expected, the symptoms may be due to mild cognitive impairment.

People with MCI may have symptoms that include:

- Forgetting things more often.

- Missing appointments or social events.

- Losing their train of thought. Or not following the plot of a book or movie.

- Trouble following a conversation.

- Trouble finding the right word or with language.

- Finding it hard to make decisions, finish a task or follow instructions.

- Trouble finding their way around places they know well.

- Poor judgment.

- Changes that are noticed by family and friends.

People with MCI also may experience:

- Depression.

- Anxiety.

- A short temper and aggression.

- A lack of interest.

When to see a doctor

Talk to your healthcare professional if you or someone close to you notices changes in memory or thinking. This may include forgetting recent events or having trouble thinking clearly.

Causes

There's no single cause of mild cognitive impairment. In some people, mild cognitive impairment is due to Alzheimer's disease. But there's no single outcome. Symptoms may remain stable for years or they may improve over time. Or mild cognitive impairment may progress to Alzheimer's disease dementia or another type of dementia.

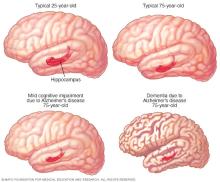

Mild cognitive impairment, also known as MCI, often involves the same types of brain changes seen in Alzheimer's disease or other dementias. But in MCI, the changes occur at a lesser degree. Some of these changes have been seen in autopsy studies of people with mild cognitive impairment.

These changes include:

- Clumps of beta-amyloid protein, called plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles of tau proteins that are seen in Alzheimer's disease.

- Microscopic clumps of a protein called Lewy bodies. These clumps are related to Parkinson's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and, sometimes, Alzheimer's disease.

- Small strokes or less blood flow through brain blood vessels.

Brain-imaging studies show that the following changes may be related to MCI:

- Decreased size of the hippocampus, an area of the brain important for memory.

- Larger size of the brain's fluid-filled spaces, known as ventricles.

- Reduced use of glucose in key brain areas. Glucose is the sugar that is the main source of energy for cells.

Risk factors

The strongest risk factors for mild cognitive impairment are:

- Older age.

- Having a form of a gene known as APOE e4. This gene also is linked to Alzheimer's disease. But having the gene doesn't guarantee a decline in thinking and memory.

Other medical conditions and lifestyle factors have been linked to a higher risk of changes in thinking, including:

- Diabetes.

- Smoking.

- High blood pressure.

- High cholesterol, especially high levels of low-density lipoprotein, known as LDL.

- Obesity.

- Depression.

- Obstructive sleep apnea.

- Hearing loss and vision loss that are not treated.

- Traumatic brain injury.

- Lack of physical exercise.

- Low education level.

- Lack of mentally or socially stimulating activities.

- Exposure to air pollution.

Complications

Complications of mild cognitive impairment include a higher risk — but not a certainty — of dementia. Overall, about 1% to 3% of older adults develop dementia every year. Studies suggest that around 10% to 15% of people with mild cognitive impairment go on to develop dementia each year.

Prevention

Mild cognitive impairment can't be prevented. But research has found that some lifestyle factors may lower the risk of getting it. These steps may offer some protection:

- Don't drink large amounts of alcohol.

- Limit exposure to air pollution.

- Reduce your risk of a head injury, such as by wearing a helmet when riding a motorcycle or bicycle.

- Don't smoke.

- Manage health conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity and depression.

- Watch your levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and get treatment if the levels are high.

- Practice good sleep habits and manage any sleep conditions.

- Eat a healthy diet full of nutrients. Include fruits and vegetables and foods low in saturated fats.

- Stay social with friends and family.

- Get moderate to vigorous exercise most days of the week.

- Wear a hearing aid if you have hearing loss.

- Get regular eye exams and treat any vision changes.

- Stimulate your mind with puzzles, games and memory training.

Diagnosis

No one test can diagnose mild cognitive impairment, also known as MCI. A diagnosis is made based on the information you provide, your medical evaluation and results of tests.

Many healthcare professionals diagnose MCI based on criteria developed by a panel of international experts:

- Changes in memory or another mental ability. People with MCI may have symptoms related to memory, planning, following instructions or making decisions. A healthcare professional may confirm these issues with a family member or a close friend.

- Mental ability that declines over time. This is revealed with a careful medical history. The change is confirmed by a family member or a close friend.

- Daily activities aren't affected. Symptoms may cause worry, but people with MCI are still able to live their lives as usual.

- Mental status testing shows mild changes for age and education level. These include brief tests such as the Short Test of Mental Status, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) or the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). More detailed testing may show to what degree memory has changed. The tests also may reveal the types of memory most affected and whether other mental skills are affected.

- The diagnosis isn't dementia. Symptoms aren't serious enough to be diagnosed as Alzheimer's disease dementia or another type of dementia.

Neurological exam

As part of a physical exam, a healthcare professional may test how well your brain and nervous system works. These tests can help look for conditions that affect memory and other mental abilities, such as Parkinson's disease, strokes and tumors.

The neurological exam may test:

- Reflexes.

- Eye movements.

- Walking and balance.

If MCI is thought to be due to mild Alzheimer's disease, tests can check for biomarkers. Biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease include the buildup of proteins in the brain. These proteins can be found in samples of blood or the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. Biomarkers also can be found in scans of the brain. If biomarkers are present, MCI symptoms may be a sign of mild Alzheimer's disease.

Lab tests

Blood tests can help rule out some physical causes of memory loss. This can include too little vitamin B-12 or thyroid hormone.

Blood tests also can check for proteins in the brain that are related to Alzheimer's disease. A sample of the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord may be removed and checked for proteins related to Alzheimer's disease. This test may confirm Alzheimer's as a cause of cognitive impairment.

Brain imaging

An MRI or CT scan can check for a brain tumor, stroke or bleeding. Positron emission tomography (PET) can look for protein buildup related to Alzheimer's disease.

Mental status testing

Short forms of mental status testing can be done in about 10 minutes. The test will ask to name the date and follow written instructions.

Longer forms of the tests look at how a person's mental abilities compare with others of a similar age and education. These tests also may find patterns of change that offer clues about the cause of symptoms.

Treatment

Treatment for mild cognitive impairment may include medicines for Alzheimer's disease. If memory symptoms are being caused by medicines or health conditions, treatment involves addressing those issues.

Mild cognitive impairment, also known as MCI, is an active area of research. Clinical studies are being conducted to better understand the condition and find treatments to improve symptoms or prevent or delay dementia.

Alzheimer's disease medicines

Your healthcare professional may recommend medicines approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to slow the decline in thinking and mental abilities. The medicines can help prevent proteins from clumping and forming structures known as amyloid plaques in the brain. Before starting treatment, the FDA recommends getting a brain MRI.

The medicines are approved for people with mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease and mild Alzheimer's disease. Known as monoclonal antibodies, they include:

- Lecanemab-irmb (Leqembi). This medicine is given as an IV infusion every two weeks. It can cause infusion-related side effects such as fever, flu-like symptoms, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, changes in heart rate and trouble breathing.

- Donanemab-azbt (Kisunla). This medicine is given as an IV infusion every four weeks. Side effects may include flu-like symptoms, nausea, vomiting, headache, trouble breathing and changes in blood pressure.

These medicines also can have more-serious side effects. Lecanemab or donanemab can cause swelling in the brain or small bleeds in the brain. Rarely, brain swelling can cause seizures or other symptoms, or even death.

People with a form of a gene known as APOE e4 appear to be at higher risk of serious side effects. The FDA recommends that you get tested for the gene before starting treatment. Once you're taking the medicine, regular brain MRIs monitor for brain swelling and bleeding.

Blood thinners also can raise the risk of bleeding in the brain when taking these medicines. Talk to your healthcare professional if you take a blood thinner before you take lecanemab or donanemab. Also talk to your healthcare professional if you have other risk factors of bleeding in the brain.

Research on other potential side effects of these medicines is ongoing.

Researchers also are studying how effective the medicines may be for people at risk of Alzheimer's disease. This includes first-degree relatives of people with the disease, such as a parent or sibling.

If memory loss is the main symptom of MCI, sometimes cholinesterase inhibitors are prescribed. But these medicines aren't recommended for routine treatment of MCI. They haven't been found to help prevent dementia, and they can cause side effects.

Treating reversible causes of MCI: Stopping certain medicines

Symptoms of MCI can be caused by certain medicines that have side effects that affect thinking. These side effects are thought to go away once the medicine is stopped. Discuss any side effects with your healthcare team. Never stop taking your medicine unless your healthcare professional tells you to do so. These medicines include:

- Benzodiazepines, used to treat conditions such as anxiety, seizures and sleep symptoms.

- Anticholinergics, which affect chemicals in the nervous system to treat many different types of conditions.

- Antihistamines, often used to manage allergy symptoms.

- Opioids, often used to treat pain.

- Proton pump inhibitors, often used to treat reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Treating reversible causes of MCI: Treating other conditions

Other common conditions besides MCI can make you feel forgetful or less mentally sharp than usual. Treating these conditions can help improve your memory and overall mental ability. Conditions that can affect memory include:

- High blood pressure. People with MCI tend to be more likely to have changes to the blood vessels inside their brains. High blood pressure can worsen these problems and may cause memory loss. Your healthcare team monitors your blood pressure and can recommend steps to lower it if it's too high.

- Depression. Depression can make someone forgetful and mentally "foggy." Depression is common in people with MCI. Treating depression may help improve memory, while making it easier to cope with the changes in your life.

- Sleep apnea. In this condition, breathing stops and starts several times during sleep, interfering with getting a good night's rest. Sleep apnea can make you feel very tired during the day, forgetful and not able to focus. Treatment can improve these symptoms and make you more alert during the day.

Alternative medicine

Some supplements have been suggested to help prevent or delay mild cognitive impairment. However, more research is needed in this area. Talk to a member of your healthcare team before taking supplements because they can interact with your current medicines.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Study results have been mixed about whether diet, exercise or other healthy lifestyle choices can prevent or reverse mild cognitive impairment. Regardless, these healthy choices promote good overall health and may play a role in good brain health.

- Regular physical exercise has known benefits for heart health. It also may help prevent or slow a decline in thinking skills.

- A diet low in fat and rich in fruits and vegetables is another heart-healthy choice that also may help protect brain health.

- Omega-3 fatty acids are good for the heart. Most research on omega-3s that shows a possible benefit for brain health looks at how much fish people eat.

- Keeping your brain active may prevent a decline in thinking skills. Studies have shown that playing games, playing an instrument, reading books and other activities may help preserve brain function.

- Being social may make life more satisfying, help preserve mental abilities and slow mental decline.

- Memory training and other cognitive training may help improve your symptoms.

Preparing for an appointment

You're likely to start by seeing your healthcare professional. If it's suspected that you have memory changes, you may be referred to a specialist. This specialist may be a neurologist, psychiatrist or neuropsychologist.

Because appointments can be brief and there's often a lot to talk about, it's good to be well prepared. Here are some ideas to help you get ready for your appointment and know what to expect.

What you can do

- Be aware of any pre-appointment restrictions. Ask if you need to fast for bloodwork or if you need to do anything else to prepare for tests.

- Write down all of your symptoms. Include details about what's causing your concern about your memory or mental ability. Include the most important examples of memory changes. Try to remember when you first started to notice changes. Also note if you think your symptoms are getting worse and why.

- Take along a family member or friend, if possible. Input from a relative or trusted friend can confirm that your memory loss is noticed by others. Having someone along also can help you remember all the information provided during your appointment.

- Make a list of your other medical conditions. Let your healthcare professional know if you're being treated for diabetes, heart disease, past strokes or any other conditions.

- Make a list of all your medicines and doses. Include prescription medicines, medicines available without a prescription, vitamins or supplements.

Questions to ask your doctor

List your questions from most pressing to least important in case time runs out. For mild cognitive impairment, some questions to ask include:

- Do I have memory symptoms?

- What's causing my symptoms?

- What tests do I need?

- Do I need to see a specialist? Will my insurance cover it?

- Are treatments available?

- Are there any clinical trials of experimental treatments I should consider?

- Should I expect any long-term complications?

- Will my new symptoms affect how I manage my other health conditions?

- Do I need to follow any restrictions?

- Is there a generic alternative to the medicine you're giving me?

- Do you have any brochures or other printed material I can take home with me? What websites do you recommend?

Ask any other questions to clarify anything you don't understand.

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare professional is likely to have questions for you, including:

- What kinds of memory issues are you having? When did they first appear?

- Are they getting worse, or are they sometimes better and sometimes worse?

- Do you feel any sadder or more anxious than usual?

- Have you noticed any changes in the way you react to people or events?

- Have you noticed any changes in how well or how long you sleep? Do you snore?

- Do you have more energy than usual, less than usual or about the same?

- What medicines are you taking? Are you taking any vitamins or supplements?

- Do you drink alcohol? How much?

- What other medical conditions are you being treated for?

- Have you noticed any trembling or trouble walking?

- Are you having any trouble remembering your medical appointments or when to take your medicine?

- Have you had your hearing and vision tested recently?

- Did anyone else in your family ever have memory trouble? Was anyone ever diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease or dementia?

© 1998-2026 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research(MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use